Trending Now

Japanese Paintings of the Second World War

Contributor: Jenevieve Kok, Senior Executive, Curatorial Team, Defence Collective Singapore

The ideological landscape of early-Shōwa-era (1926-1989) Japan was rife with anti-Western sentiment. Fervent right-wing nationalists resented the extent of Westernisation that characterised the preceding Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926) eras. They contended that Western ideas had introduced individualism and liberalism, which contaminated Japanese culture. To rid this “contamination”, they advocated a “return to Japan” (nihon kaiki)[1] – a restoration of premodern Japanese tradition and a revival of fervent emperor veneration. These sentiments formed the foundation of Japan’s wartime ideology and propelled the creation of the military’s War Campaign Documentary Paintings (sensō sakusen kirokuga) during the Second World War (WWII, 1937-1945).[2] Often referred to as war documentary paintings (sensō kirokuga), the emergence of these paintings created a new genre of Japanese art that disappeared with the end of the war.

The Military’s War Documentary Paintings

A year after Japan’s invasion of China in 1937, the Japanese military began their War Art Programme by sending artists to various battlefronts and occupied territories to create official war documentary paintings. These commissioned war artists comprised painters who specialised in either yōga (Western-style painting) or nihonga (Japanese-style painting). Their paintings were exhibited in large military-run war art exhibitions and disseminated throughout the mass media to reach all echelons of Japanese society.

Figure 1. Tsuruta Gorō, Paratroops Descending on Palembang,

1942, oil on canvas, 194 x 255 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

The war documentary paintings were created to (1) document the war; (2) raise the wartime morale of the Japanese people; (3) garner support for the war effort; and (4) celebrate Japan’s “glorious military achievements” and preserve its history for future generations. Above all, it was imperative that Japan’s wartime ideology was embedded in these paintings. To fulfil these objectives, the military believed that the war paintings needed to be compelling, realistic, and easily understood by the masses. The yōga war artists were technically and stylistically equipped to meet these objectives, as their training in Western art enabled them to depict three-dimensional depth and render the human form with pictorial accuracy (Fig. 1). Furthermore, many yōga artists turned to premodern European realism for inspiration and infused compositional and aesthetic techniques from the genre of history painting into their works to dramatise their depictions of the contemporary war.[3]

Figure 2. Ezaki Kōhei, Capture of Guam, 1941, colour on paper,

195.5 x 271 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Conversely, the nihonga war artists’ disregard for scientific perspective gave their subjects a visual flatness, stripping the desired level of verisimilitude from their paintings (Fig. 2). Art critics further argued that the combination of nihonga’s traditional materials, such as ink and paper, and tendency for anti-naturalism made it unsuitable for portraying the contemporary war and, thus, inferior to yōga in that regard. Despite Japan’s anti-Western sentiment at the time, the military favoured yōga war painters who ultimately comprised an overwhelming majority of the War Art Programme.

Manifesting Japan’s Wartime Ideology

This article embarks on a visual analysis of several key yōga war documentary paintings, which comprised three main categories: (1) non-combat scenes of Japanese soldiers; (2) meetings of Japanese generals and the surrender of their enemies; and (3) land, aerial, and naval battles. In order to fulfil the military’s ideological aims, these paintings needed to be imbued with the tenets of wartime ideology, which included unyielding patriotism, emperor veneration, self-effacement, and obeisance to authority. At its core, the most important principles were bushidō (the way of the warrior) and the kokutai (national polity).

Believed to have developed during the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century,[4] bushidō is a martial code that functioned as the guiding principle for samurai. It was characterised as the “animating spirit” that made up the soul of the Japanese people and welcomed death “with a perfect calmness” in battle. The military increasingly espoused this idea as the war progressed and used it to instil a fighting spirit in both the soldiers on the battlefront and civilians on the “homefront”.

Akin to bushidō, the kokutai was not a new concept in Japan with its emergence in the 1820s. Confucian scholar Aizawa Seishisai [5] first conceptualised the kokutai as the “essence of the nation”, contending that Japan was a “divine land…where the sun rises”, united under a single ruler – the emperor – who descended from the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami. Refined through the decades, this idea was eventually referred to as Japan’s unique tradition of an unbroken line of emperors. The wartime ideologues believed that the kokutai made Japan culturally, spiritually, and morally superior to the West and other Asian nations. Thus, they constructed a unifying myth between the emperor and his people, creating an imagined community that envisioned Japan as one big family under the Shōwa emperor.

Japan’s wartime nationalists built on the established foundations of bushidō and the kokutai, altering its tenets to suit the ideological needs of the imminent war. By drawing on firmly entrenched codified beliefs, the kokutai and bushidō were placed at the centre of Japan’s political and spiritual systems. Together, they were powerful, pervasive, and presented as immutable principles.

Depicting the Everyday Soldier: Non-Combat War Paintings

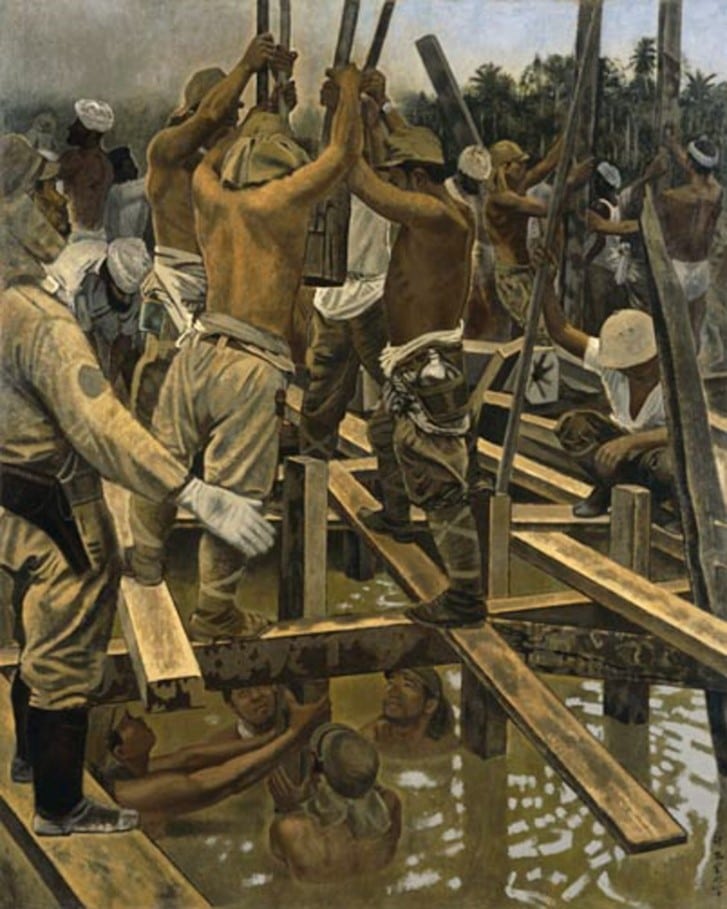

Figure 3. Shimizu Toshi, Engineering Corps Constructing a Bridge in Malaya,

c. 1944, oil on canvas, 159.5 x 128.7 cm.

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

The first category of yōga war documentary paintings comprises scenes of Japanese soldiers engaged in non-combat duties. These paintings often depict soldiers performing mundane tasks and portray their daily lives outside of battle. This category is best exemplified by Shimizu Toshi’s (1896-1945) Engineering Corps Constructing a Bridge in Malaya (Fig. 3).

The title of this work plainly explains the subject of the painting and identifies the location in which it is set, a typical feature of war documentary paintings. With a limited colour palette, Shimizu depicts several Japanese soldiers working on a bridge in Malaya, which Japan occupied after its success in the Malayan Campaign (1941-1942). The focal point of this work is the central group of soldiers, who are further split into two subgroups. With their faces largely hidden from view, four soldiers stand on narrow planks affixing a structure to a wooden block. Below them are another four soldiers who wade neck-deep in water, steadying the block for the soldiers above. These eight men are supervised by a Japanese officer wearing a sen-bou field cap on the left. Together, they work collectively and endure hard physical labour, exhibiting the valued quality of the disciplined fulfilment of one’s duty, no matter how arduous the task is. By depicting the daily lives of Japanese soldiers, Shimizu communicates the crucial values of obedience and humility in service of the emperor.

Interestingly, Shimizu includes local civilians or possibly prisoners of war in the scene. He distinguishes them from the Japanese soldiers by depicting their skin in a darker shade and dressing them in their cultural headpieces, such as the Indian pagri and Malay songkok. These men appear to work harmoniously alongside the Japanese soldiers, assisting them in the construction of the bridge. Through this inclusion, Shimizu strategically embeds Japan’s self-assigned “historic mission in Asia”. Japan believed that as the divine and superior nation, it needed to unite Asian countries under its leadership. This messianic mindset was demonstrated by its initial annexations of territories in Taiwan, Korea, and China,[6] and subsequent expansions into Southeast Asia and South Asia. These occupations constituted Japan’s plan of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. The notion of a unitary Asia stems from the idea of Pan-Asianism, which was popularised by Japanese art critic Okakura Tenshin (1862-1913) and propagated through the slogan hakkō ichiu (eight corners of the world under one roof) in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Under the guise of an anti-Western colonial rhetoric, Japan used these ideas to assert its dominion over Asia and suppress the desire for independence in these nations.

Although the painting lacks the excitement of a dynamic battle scene, Shimizu endorses the virtues of discipline and subservience through self-effacing Japanese soldiers and embeds the message that a soldier’s honour comes from the humility of his task. This work also serves to inspire the same virtues in its Japanese viewers. Crucially, its unassuming imagery presents a positive spin on the relationship between the Japanese soldiers and the locals in Japan’s occupied territories, which in reality was the complete opposite.

Japanese Generals and the Surrender of Their Enemies

To attest to their success in the war, the military commissioned several paintings that depicted meetings of Japanese generals negotiating the surrender of their Allied enemies. These paintings simultaneously document Japan’s victory and emphasise the antithesis between Japan’s strength and the weakness of their Western foes. A prime example of these paintings is Miyamoto Saburō’s (1905-1974) Meeting of Generals Yamashita and Percival (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Miyamoto Saburō, Meeting of Generals Yamashita and Percival,

1942, oil on canvas, 180.7 x 225.5 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Painted in 1942, Miyamoto depicts the unconditional surrender of the British army to the Japanese at the Ford Motor Factory following the Battle of Singapore (1942). General Yamashita Tomoyuki (1885-1946) sits across a broad table from Lieutenant-General Arthur E. Percival (1887-1966), the commander of the British forces in Singapore. Before Miyamoto painted this famous scene, a photograph of the surrender was captured and published in the Japanese newspapers (Fig. 5). A simple comparison reveals that he had likely based his painting on the photograph. He was also not there to witness the surrender himself. However, Miyamoto’s work is far from a mere reproduction of the photograph.

Figure 5. Photograph of the surrender of Singapore at the Former Ford Factory in Bukit Timah Road, 1942, size unknown.

Lim Kheng Chye Collection from Shashin Shūhō.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The overarching themes of the artist’s work express (1) the strength of Japan’s military; (2) the weakness of the West; and (3) the contrast between perceived Japanese superiority and Western inferiority. He uses colour, composition, and the inclusion of specific objects to simultaneously enhance the appearance of Japan’s strength and exaggerate Britain’s weakness.

Miyamoto employs an elevated perspective that visually enlarges what was originally a cramped room, and his diagonal composition creates a sense of tension between the two groups in the confined space. He illustrates the imbalance of power between the Japanese and British by placing Yamashita and his officers on the high end of the table, while Percival and his men occupy the lower end. This imbalance is heightened by their contrasting postures and expressions.

In the centre of the painting, Yamashita sits upright with a stiffly bent arm, clenched fist, and a resolute expression in his face as he unblinkingly stares at Percival. This is one of the most immediate instances of Miyamoto’s representation of Japan’s military strength and success. Interestingly, Yamashita’s posture is a significant deviation from the original photograph, reflecting the artist’s attempt to intensify Yamashita’s imposing presence in the room. The rigid postural lines of the Japanese commanders sharply contrast Percival and his men, who apprehensively lean towards each other and appear to avoid eye contact with the Japanese. Miyamoto effectively portrays the inferiority of the British by diminishing both their presence in the room and bodily proportion in the painting.

The juxtaposition between their positions at the table are supplemented by the colours and textures of their uniforms. The Japanese commanders are formally dressed in dark uniforms, which are ornamented with their insignias and aiguilettes. Conversely, Percival and his officers wear plain, light beige garments that are depicted in a dishevelled manner with wrinkles and creases. The soft appearance of their uniforms reinforces the feeling of uncertainty among the British commanders. Miyamoto’s portrayal of the British effectively “degrades the enemy” whilst elevating the Japanese.

On the top right, Miyamoto intriguingly depicts the Union Jack and a white surrender flag in the corner of the room. These flags were not featured in the original photograph and exemplify another noteworthy attempt to dramatise the scene. As if mimicking the British commanders, the wrinkled flags lean lifelessly on the wall and represent the British army’s devastating defeat. Furthermore, this extends the contrast between the visual rigidity of Yamashita’s side of the table and the somatic softness on Percival’s end.

Miyamoto’s creative addition of the flags is not his only artistic inclusion to his interpretation of the scene. Two pieces of headgear are diagonally situated on the wide table. One is a sen-bou field cap placed flat on the table, while the other is a British Brodie helmet that sits upturned. Like a defenceless tortoise flipped upside-down, the exposed helmet symbolises the vulnerability of the British in their surrender. Miyamoto mirrors the outcome of Japan’s successful invasion and the dynamic between the two groups in the room through the deliberately positioned headgear.

The artist’s careful composition gave the original scene in the news photograph an expressive quality that the camera could not capture, one that is often absent in reality. Miyamoto utilised visual and symbolic contrasts to strengthen the message of Japan’s superiority against Western inferiority. Interestingly, this painting recalls Japan’s early-twentieth-century goal when it strove to attain a “seat at the world table” and stand as equals with the West.[7] This painting demonstrates that not only has Japan gained its seat at the table, but it is also seated in a position of superiority and dominance over a Western nation. Thus, Miyamoto’s powerful portrayal goes beyond the documentation of events by emblematising Japan’s new role on the global stage.

The Japanese Fighting Spirit

The largest portion of war documentary paintings constitute battle scenes, which are further divided into subgroups of aerial, naval, and land conflicts. Within this category, the artists’ style and compositional strategies varied depending on the type of battle.

Aerial and naval battles were often depicted together in paintings due to the nature of combat. They were usually filled with action and emphasised the movement of Japanese aircraft or warships from an aerial perspective. The artworks by Nakamura Ken’ichi (Fig. 6) and Ishikawa Toraji (Fig. 7) are quintessential examples of aerial and naval war documentary paintings.

To convey a sense of action, Nakamura uses clouds of trailing smoke that follow the planes to indicate the swift speed of the aircraft. He further dramatises the scene through pillars of smoke arising from the ships or water plumes emanating from the sea. In Ishikawa’s aerial scene, he exaggerates the movement of Mitsubishi G3M bombers with a whirling sky and choppy sea. Although these works were filled with dynamism, several Japanese art critics criticised the lack of artistic variation. For instance, Araki Hedeo found the panoramic bird’s-eye-view composition to be lacklustre and repetitive. He also expressed his discontent with the monotony of artistic devices employed to indicate action.

Figure 6. Nakamura Ken’ichi, Naval Battle Off Malaya, 1942, oil on canvas,

192 x 257.5 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Figure 7. Ishikawa Toraji, Transoceanic Bombing, 1941, oil on canvas,

165 x 202.5 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Land battles made up the majority of the artworks within the category of battle paintings. Amongst the numerous scenes of soldiers fighting on the battlefields, there is one painting that garnered substantial acclaim from both the military and Japanese public.

Figure 8. Fujita Tsuguharu, Final Fighting on Attu, 1943, oil on canvas,

193.5 x 259.5 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

In Final Fighting on Attu (Fig. 8) Fujita Tsuguharu (1886-1968) depicts the eponymous Battle of Attu (1943) that ended with the crushing defeat of the Japanese army. On the eve of their defeat, Colonel Yamasaki led his surviving troops in a final banzai charge. Fujita’s interpretation of their final stand manifested in a muddy monochromatic mesh of overlapping bodies. Almost indistinguishable, Japanese and American soldiers engage in uncomfortably close hand-to-hand combat. While the artist instils an indomitable fighting spirit through the exaggerated ferocity of the Japanese soldiers, his work most effectively expresses self-sacrifice in the face of impending death.

Fujita’s masterful rendering of minute details, such as the soldiers’ shoelaces, canteens, and detailing on their uniforms, attests to his wartime reputation as the most prominent war documentary painter. Although the monochromatic brown dominates the canvas, Fujita subtly adds specks of colour amidst the chaos. An unusual example of this is found in the sprinkling of purple and pink flowers on the battlefield in between the overlapping soldiers. The surprising inclusion of these flowers juxtaposes the overall morbidity of the scene, as if evoking the idea of life in death. He also balances the constrained space of the overlapping bodies with an expansive backdrop of the mountains.

Figure 9. Detail view of Fujita Tsuguharu, Final Fighting on Attu.

The most intriguing feature of Fujita’s Attu is the depiction of Japanese shin guntō (new military swords) (Fig. 9). These swords were contemporary versions of samurai katana swords and were issued to commissioned and non-commissioned officers during the war. In Fujita’s work, the shin guntō are wielded by several soldiers, which create diagonal paths across the painting and provide a counterbalance to the disarray of the scene. These swords demonstrate his allusion to Japan’s traditional samurai heritage and the martial ethic of bushidō.

During the war, the military coupled the bushidō with the concept of gyokusai. Literally translated to “smashed jewels”, the military drew from sixth-century Chinese texts and conceived the term to moralise the action of self-sacrifice. Gyokusai referred to the idea that it was a soldier’s honourable duty to die heroically in battle rather than surrender. [8] The military incorporated the term into the wartime vernacular and romanticised the idea of choosing death over dishonourable surrender, buttressing gyokusai against the steadfast roots of bushidō. Fujita illustrates this through Colonel Yamasaki’s final banzai charge. Facing certain defeat, Yamasaki and his troops chose an honourable death over surrender to the American forces. This idea is further complemented by the shin guntō. Viewed in totality, this painting communicates the message that regardless of rank, every Japanese soldier should bravely fight till the end for the nation and his emperor.

Final Fighting on Attu epitomises the Japanese fighting spirit that the military was so eager to convey. Despite the painting’s chaotic and violent imagery, it garnered favourable responses from the Japanese public, and it surprisingly became a site for people to honour the dead. Yamagiwa Yasushi stated in the Asahi newspaper that Attu “admirably met the nation’s need to visualise this traumatic event and witness the bloody battlefield”, encouraging viewers to examine its intricate realism. One would think that the painting’s mesh of dead bodies would demoralise its Japanese viewers. However, much like the tale of the Spartans at the Hot Gates of Thermopylae, Fujita’s visceral work bolstered the people’s morale and inspired them to persevere till the end. The power of the painting stems from both Fujita’s arresting imagery and his allusion to a historically symbolic weapon. He taps into firmly established Japanese concepts that have been etched in the minds of the people through the centuries.

The power of these yōga war documentary paintings emerges from its enthralling, dynamic, and realistic imagery. Despite their varied subject matter and style, the war artists powerfully embedded facets of Japan’s wartime ideology by tapping into propagated principles and alluding to historically potent symbols. However, what made their works truly compelling was the duality of memorialisation and documentation within each painting. While this was partly due to their adoption of Western realism, it also stems from the symbolic and somatic elevation of the Japanese soldiers in their paintings. The war artists deconstructed the complex concepts of wartime ideology and presented it in a manner that was comprehensible to the general Japanese public. They depicted codified imagery that carried well-established meanings and propelled the nationalistic fervour of wartime Japan. Although the paintings’ propagandistic intent was clear, they were able to evocatively depict Japanese soldiers and scenes of war in a manner that enabled their viewers to resonate with the subject matter before them.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London; New York: Verso, 2006. https://hdl-handle-net.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/2027/heb.01609.

- Benesch, Oleg. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushidō in Modern Japan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198706625.001.0001.

- Connelly, Mark. “The Issue of Surrender in the Malayan Campaign, 1941-2.” In How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender, edited by Holger Afflerbach and Hew Strachan, 341-50. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://academic.oup.com/book/32546/chapter/270333181.

- Doak, Kevin. A History of Nationalism in Modern Japan: Placing the People. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2007. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1163/ej.9789004155985.i-292.

- Ikeda, Asato, Aya Louisa McDonald, and Ming Tiampo, eds. Art and War in Japan and Its Empire. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2012.

- Ikeda, Asato, The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art during the Second World War. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018.

- Hall, Robert King, ed. Kokutai No Hongi: Cardinal Principles of the National Entity of Japan. Translated by John Own Gauntlett. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1949. https://ebin.pub/kokutai-no-hongi-cardinal-principles-of-the-national-entity-of-japan-9780674284869-0674284860.html.

- Hanneman, Mary L. Japan Faces the World, 1925-1952. London; New York: Routledge, 2001. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.4324/9781315839134.

- Maruyama, Masao. Thought and Behaviour in Modern Japanese Politics. London: Oxford University Press, 1969. https://hdl-handle-net.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/2027/heb02408.0001.001.

- Mead, Claire. “Akabane Swords and the end of the Second World War.” Imperial War Museums. Published September 28, 2020. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.iwm.org.uk/blog/partnerships/2020/09/akabane-swords-and-end-second-world-war-guest-blog-claire-mead.

- Saaler, Sven and J Victor Koschmann. Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.4324/9780203965467.

- Starrs, Roy. Rethinking Japanese Modernism. Leiden; Boston: Global Oriental, 2012. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1163/9789004211308.

- Shillony, Ben-Ami. Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198202608.001.0001.

- Tansman, Alan. The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism. California: University of California Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520245051.001.0001.

- Tsuruya, Mayu. “Sensō Sakusen Kirokuga (War Campaign Documentary Painting): Japan’s National Imagery of the “Holy War,” 1937-1945.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2005. ProQuest (3224057). http://libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/dissertations-theses/i-sensô-sakusen-kirokuga-war-campaign-documentary/docview/305412177/se-2.

- Van Orden, Mike. “The Forgotten Battle of Attu.” The Saber and Scroll Journal 3, no. 4 (2014): 109-24. https://saberandscroll.scholasticahq.com/article/28566.

- Winther-Tamaki, Bert. “Embodiment/Disembodiment: Japanese Painting During the Fifteen-Year War.” Monumenta Nipponica 52, no. 2 (1997): 145-80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2385570.

- ———. Maximum Embodiment: Yōga, the Western Painting of Japan, 1912 -1955. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2012. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqdth.1.

Endnotes

[1] The term “return to Japan” first appeared in Hagiwara Sakutarō’s essay “Return to Japan” (Nihon e no kaiki) written in 1938 as a way to overcome modernity and the West.

[2] Japan’s conflicts from the 1930s to 1945 have been identified by several names such as “The Fifteen-Year War” (1931-1945), “The Second-Sino Japanese War” (1937-1945), and “The Asia-Pacific War” (1941-1945). However, this article takes the stance that WWII began with Japan’s invasion of China in 1937.

[3] In this article, “contemporary” refers to the period from the 1930s to the 1940s.

[4] The popular belief is that bushidō developed in the twelfth century with the emergence of the samurai warrior class. However, research has shown that they were too concerned with battles to formally establish the concept. Additionally, many samurai were only truly loyal to their daimyō (feudal lords) as long as it benefitted them. There is also no definitive evidence that there was a universally accepted definition of bushidō before the Meiji era.

[5] Aizawa Seishisai was a scholar from the Mito School (Mitogaku) during the Edo era (1603-1867) who, along with his Mito colleagues, were in favour of restoring imperial rule to Japan and played a significant role in the development of the kokutai.

[6] While the height of Japan’s territorial expansion occurred during WWII, it began its imperial conquests in the 1890s with Taiwan as its first colony.

[7] Japan’s rapid modernisation after 1868 was propelled by its desire to establish itself as a military and imperial powerhouse. With its resounding victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), Japan surprised the Western world and was acknowledged as the leading power in Asia. Japan believed that it had finally earned the right to be treated as an equal alongside the Western nations in the early twentieth century. However, when the time came, it was instead faced with exclusionary acts and discriminatory international policies.

[8] The sixth-century Chronicles of Northern Qi describes the story of a Western Wei prince who, along with his clan, was killed because of his refusal capitulate to the triumphant Gao clan. The prince asserted that he would rather be smashed like a jade rather than compromise his integrity and bend the knee to the Gao clan.